Shakespeare and the Elephant

The Bard's Views on the Human Mind Are More Like Khaneman's and Haidt's than Freud's

Because literary critics have used Freud’s ideas about mind and behavior so extensively in interpreting Shakespeare, I proposed in my previous post that Shakespeare was no Freudian. By that I meant that I have found nothing in his writings that anticipated Freud’s theories of the mind, and therefore we don’t need psychoanalytic theory to understand the Bard’s works. Moreover, I suggest that Shakespeare’s references to what we now call the “unconscious” comport better with modern models of the unconscious than with Freud’s century-old teachings.

Problems with Psychoanalytic Theory

Freud’s work rests on the notion of a mind divided into three parts at war with each other. The id, he said, is the unconscious, which derives its energy from the dark instincts of sexual desire and aggression. The superego is the conscience: a strict disciplinarian and the blue-nosed moralist of the mind, reflecting the shalt-nots imposed by parents, teachers, priests, and other authorities. It therefore falls to the mostly-conscious ego to keep peace among the mind’s parts by suppressing or redirecting the id’s forbidden desires, satisfying the superego’s strictures, and simultaneously helping the individual negotiate pressures imposed by the external world. The Freudian mind is not a happy place, and many modern psychologists and neuroscientists see things quite differently, thanks to a century of post-Freudian research.

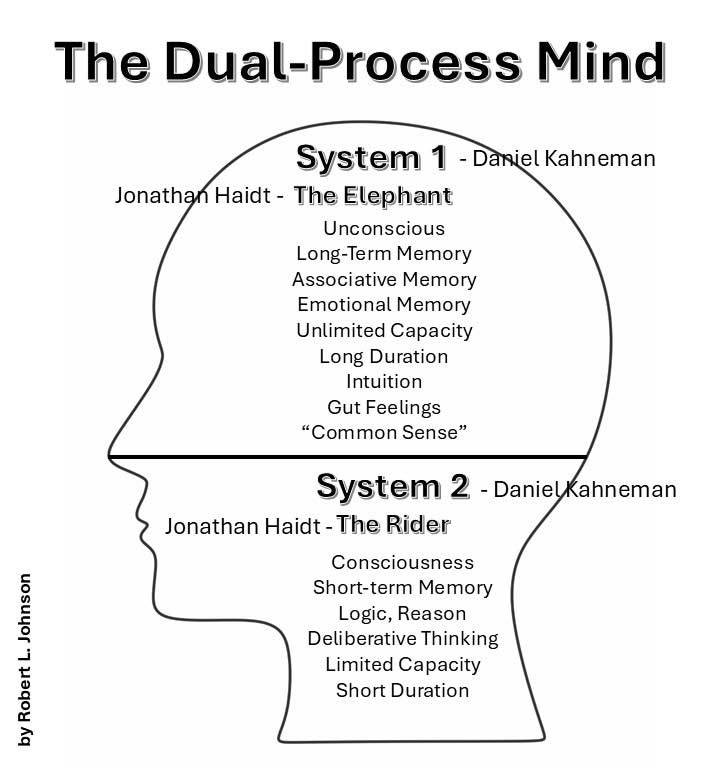

In my opinion, the best and most accessible descriptions of the modern view come from books by two psychological luminaries: social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, who specializes in the psychology of morality, and the late Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel prize winner who studied the flaws and biases in human decision-making. My summaries of their positions, below, will be necessarily brief, so I refer you to visit their writings in person.

System 1

Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow,1 describes a two-part (dual-process) mind in which the major partition, System 1, is unconscious. Its contents are more and less accessible, but its apparatus operates outside of our awareness. Fundamentally, it consists of what psychologists call long-term memory, the mental storehouse for a lifetime of facts, events, ideas, skills, habits, and language.2 Its capacity is vast—seemingly unlimited, except in cases such as brain damage or dementia.

System 1, however, lacks the ability to “think” in the usual sense—that is, it cannot do calculations, make plans, or create complex ideas. Nor is it at “war” with the rest of the mind. But it does have one superpower—which is to form chains of connections among items in memory that feature similar patterns or are tagged with similar emotions. This ability, known as associative memory, allows us to retrieve memories, say, of a friend’s name, a familiar face, or details of a vacation in Maui, with lightning speed.3

This “fast thinking” System 1 also conveys the power to recognize and react almost instantaneously to imminent danger or an opportunity. It specializes in the sort of “instinctual” thinking that enables us to quickly steer a car around an obstacle that suddenly appears in the road—an ability that we might call a “gut reaction.” This same ability can also rapidly draw from memory the complex knowledge that we call “expertise”—the sort of knowledge that your physician calls up when making a diagnosis based on a well-learned pattern of symptoms, seemingly without much slow and deliberate thought. In such instances, we might refer to it as intuition.

Intuitive thinking, however, is not always reliable, for it can easily insert biases, prejudices, and misinformation into our thinking.4 Shakespeare makes much of these mental flaws in his plays when characters jump to unwarranted conclusions.5 We see this, for example, when Prince Hal and Poins fool Falstaff into thinking they are dangerous robbers6 or in Othello when Cassio’s possession of the handkerchief confirms Desdemona’s infidelity in Othello’s mind, and Iago privately gloats about it, saying to himself:

Trifles light as air Are to the jealous confirmations strong As proofs of holy writ - Othello, 3.3.322

Another example comes from Much Ado About Nothing, where Antonio and Leonato quickly confirm their wrongful suspicions about Claudio’s guilt for Hero’s apparent death. Psychologists call this confirmation bias.

On the other hand, the intuitive “thinking” of System 1 can be helpful—even life-saving, as it possibly was for your ancient ancestor whose fear response was triggered upon noticing unnatural movements in the grass made by a lurking lion at the waterhole. System 1, then, can react quickly, alerting us to possible danger—which illustrates another feature of this unconscious mind: its intimate association with the emotional circuitry of the brain. Evolution has wired us to remember events associated with strong emotions—in contradiction with Freud’s suggestion that we often repress threatening experiences.

System 2

The second part of the human mind is the one with which we are most familiar: our consciousness. It is the process that we think of as our “self”—who we (think we) really are.

Unlike unconscious processing, conscious thought is slow. As you have already guessed, Kahneman called it System 2, while other psychologists know it as short-term memory. By any name, this portion of the mind is the one capable of logic and reason. Yet, it is also influenced by associations pushed into consciousness from System 1. In this way, System 2 provides much of the raw material for new ideas and creative thinking.

Again in contrast with the vast storehouse of System 1, short-term memory has an extremely limited capacity (typically only about 7 items!), so it has no room for permanent storage. Accordingly, it was no accident that phone numbers, in the days before area codes, were seven digits long.7 Likewise, studies show that a bit of information—a single digit, for example—lasts only about 30 seconds in System 2 unless it is refreshed by external stimuli or associated with existing memories from the internal storage of System 1. The small capacity and short duration of memories in System 2 explain why meaningless material, such as a phone number or an unfamiliar name, is so difficult to remember after even a short delay.

What exactly is the job of System 2? Let’s call it deliberative thinking. That is, System 2 allows us to discover new relationships and make new connections among items served up by long-term memory or by experience. In other words, System 2’s job is to make things meaningful in terms of previous experiences stored in unconscious memory. If System 2 can do its job, it will deliver those newly contexted ideas to long-term memory for storage.8 If not, the information is forgotten.

The Elephant and the Rider

Jonathan Haidt’s book, The Righteous Mind, lays out a clever metaphor for Systems 1 and 2. which he likens to an elephant and its rider traveling through the forest.9 (See the figure below.) Thus, the mind’s Elephant (System 1) is the quick-thinking, intuitive partition, while the Rider (System 2) is the deliberative, rational, slower-thinking department of the mind, The Rider, of course, thinks he (or she) is in charge, but it is the intuitive Elephant who usually determines which path to take, leaving the slow-thinking Rider to rationalize the “choice.”

To see how this applies to Shakespeare, consider how the Rider in Falstaff’s mind justifies his Elephant’s love of sack:10

. . . A good sherris sack hath a two-fold operation in it. It ascends me into the brain, dries me there all the foolish and dull and crudy vapors which environ it, makes it apprehensive, quick, forgetive, full of nimble, fiery, and delectable shapes, which, delivered o’er to the voice, the tongue, which is the birth, becomes excellent wit. The second property of your excellent sherris is the warming of the blood, which, before cold and settled, left the liver white and pale, which is the badge of pusillanimity and cowardice. But the sherris warms it and makes it course from the inwards to the parts’ extremes. It illumineth the face, which as a beacon gives warning to all the rest of this little kingdom, man, to arm; and then the vital commoners and inland petty spirits muster me all to their captain, the heart, who, great and puffed up with this retinue, doth any deed of courage, and this valor comes of sherris. So that skill in the weapon is nothing without sack, for that sets it a-work; and learning a mere hoard of gold kept by a devil till sack commences it and sets it in act and use. Hereof comes it that Prince Harry is valiant, for the cold blood he did naturally inherit of his father he hath, like lean, sterile, and bare land, manured, husbanded, and tilled with excellent endeavor of drinking good and good store of fertile sherris, that he is become very hot and valiant. If I had a thousand sons, the first human principle I would teach them should be to forswear thin potations and to addict themselves to sack. - Henry IV, Part 2, 4.2.99-129

Sleep and Dreams

I submit to you that System 1 is also the part of the mind that is active when we dream. During a dream state, we experience a consciousness largely restricted to the internal world, yet free from our waking needs for sense and reason. Dreaming, then, is a state of consciousness that freely allows access to a stream of connected memories and associations from the unconscious mind. Dreaming is also a mental state that obviously fascinated Will Shakespeare, to whom the dream state must have seemed like an improv theater in the mind. He not only wrote an entire play about sleep and dreaming on a midsummer’s night, but he mentioned sleep and/or dreaming in every play he wrote.

As for Freud, I disagree with most of his dream analysis. Yet, I do think that he was (partly) right in calling dreams the “royal road to the unconscious”11 in the sense that the kaleidoscopic changes of the images, topics, and storyline in a dream reflect the associations that connect the contents of our unconscious. Of this the Bard was supremely aware—and so, he serves up dream sequences in which Bottom suddenly has the head of an ass or Hermia dreams that a serpent is crawling on her breast and eating her heart. Our dual-process interpretation of such bizarre dream sequences suggests that they emerge from the web of associations in System 1 memory.

To conclude, I reiterate that Shakespeare’s understanding of the mind was more consistent with Kahneman and Haidt than it was with Freud, although I would not argue that the Bard pioneered either perspective. In fact, the pair with which his model of the mind was most congruent were the ancient physician Galen and the even older philosopher Aristotle.

And finally, I must confess the suspicion that, had the Bard somehow known of Freud’s theories, he might have embraced them for their dramatic qualities. After all, it sounds more poetic to attribute, say, Macbeth’s downfall to an internal, three-sided war involving his id, ego, and superego than it does to blame the Thane of Cawdor’s Elephant.

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider getting a copy of our book, Psychology According to Shakespeare, by Philip Zimbardo and me (published in 2024 by Prometheus Books and available at bookstores everywhere).

Here is a peek at the table of contents, showing the featured plays that illustrate each psychological topic:

Psychology According to Shakespeare

Prologue – Why Shakespeare and Psychology?

Introduction – Shakespeare’s Psychology and the Roots of Genius

Part I: Nature vs. Nurture

Chapter 1 – Nature-Nurture, Neuroscience, and the Brain of the Bard: The Tempest

Chapter 2 – The Ages and Stages of Man (and Woman): As You Like It

Part II: The Person vs. the Situation

Chapter 3 – Henrys, Humors, and the Psychology of Personality: Richard II – Henry V

Chapter 4 – Social Influence from Stratford to Stanford: Measure for Measure

Chapter 5 – Heroes Ancient and Modern, Major and Minor: Othello

Part III: Into the Mind

Chapter 6 – Sleep and Dreams: A Window into the Unconscious: A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Chapter 7 – Mental Illness and Other Ill Humors: Richard III

Part IV: Reason vs. Emotion

Chapter 8 – Emotion, Motivation, and Elizabethan Love: Love’s Labour’s Lost

Chapter 9 – Reason, Intuition, and the Dithering Prince of Denmark: Hamlet

Epilogue – Psychology, Shakespeare, and Beyond

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

The brain does many other things outside of consciousness—and outside of System 1. For example, we don’t have to consciously regulate our body temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate or think about releasing adrenaline when we are excited; these functions are regulated automatically and unconsciously. Likewise, there are many complex movements that we can make—walking, talking, and perhaps a golf swing—that we can trigger consciously but which unconscious processes carry out automatically; ironically, we may perform such activities more poorly when we consciously think about them.

Associative memory also helps us link seemingly unrelated items, such as a name and a face, that have a third element in common, such as an event. This is also a function that computers do not do as easily as the brain . . . yet.

It seems to me that when people label a pet notion as “common sense,” that is a signal that they have not given it much thought. Rather they are simply sharing the biases and prejudices stored among their memories in System 1.

For more on the cognitive biases known to Wm. Shakespeare, see our book:

Zimbardo, Philip, and Robert Johnson. Psychology According to Shakespeare. Lanham, MD: Prometheus Books, 2024.

and

Parvini, Neema. Shakespeare and Cognition: Thinking Fast and Slow Through Character. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Henry IV, Part 1, 2.2.

Psychologists have found that grouping numbers or words or other items into clusters or “chunks” helps us retain them in short-term memory, at least for a while. The phone company quickly took advantage of “chunking” by adding hyphens to help us group the digits of phone numbers into “chunks.” The same process explains the ease with which we “chunk” letters into words.

For more information about the structure and function of memory, see an introductory psychology text, preferably Psychology: Core Concepts, written by Philip Zimbardo, Vivian McCann, and me.

Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books, 2012.

Sack is a sweet, fortified wine similar to sherry.

Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939 and James Strachey. The Interpretation of Dreams. Basic Books A Member of the Perseus Books Group, 2010.

Stunning, my friend. Absolutely stunning.