You and Will Shakespeare Walk into a Pub . . .

How the Bard and His Audiences Thought About Their World

King James I and Queen Elizabeth I - portraits courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Imagine yourself as a denizen of London in Elizabethan times,1 some four hundred years ago. If you were among the gentry or noble classes, life was good, particularly because it was an era of relative peace among the previously warring English nobles.

For the working classes (and especially for men), pubs would have been social centers of their lives, where a thirsty fellow could get food, drink, and even lodging.2 In comparison with the London pubs of today, however, the Elizabethan versions were more odiferous and more likely to have female companionship for sale. They could be rowdy places, but thirsty Elizabethans would find much that is familiar in the watering holes of modern London.

If you had accompanied Will Shakespeare for a pint at The Anchor, you would have been in lively company. According to his friend, playwright Ben Jonson, Will Shakespeare was “of an open and free nature; had an excellent fancy, brave notions, and gentle expressions, wherein he flowed with that facility that sometime it was necessary he should be stopped.” Jonson added, “His wit was in his own power; would the rule of it had been so too. Many times he fell into those things, could not escape laughter.”3

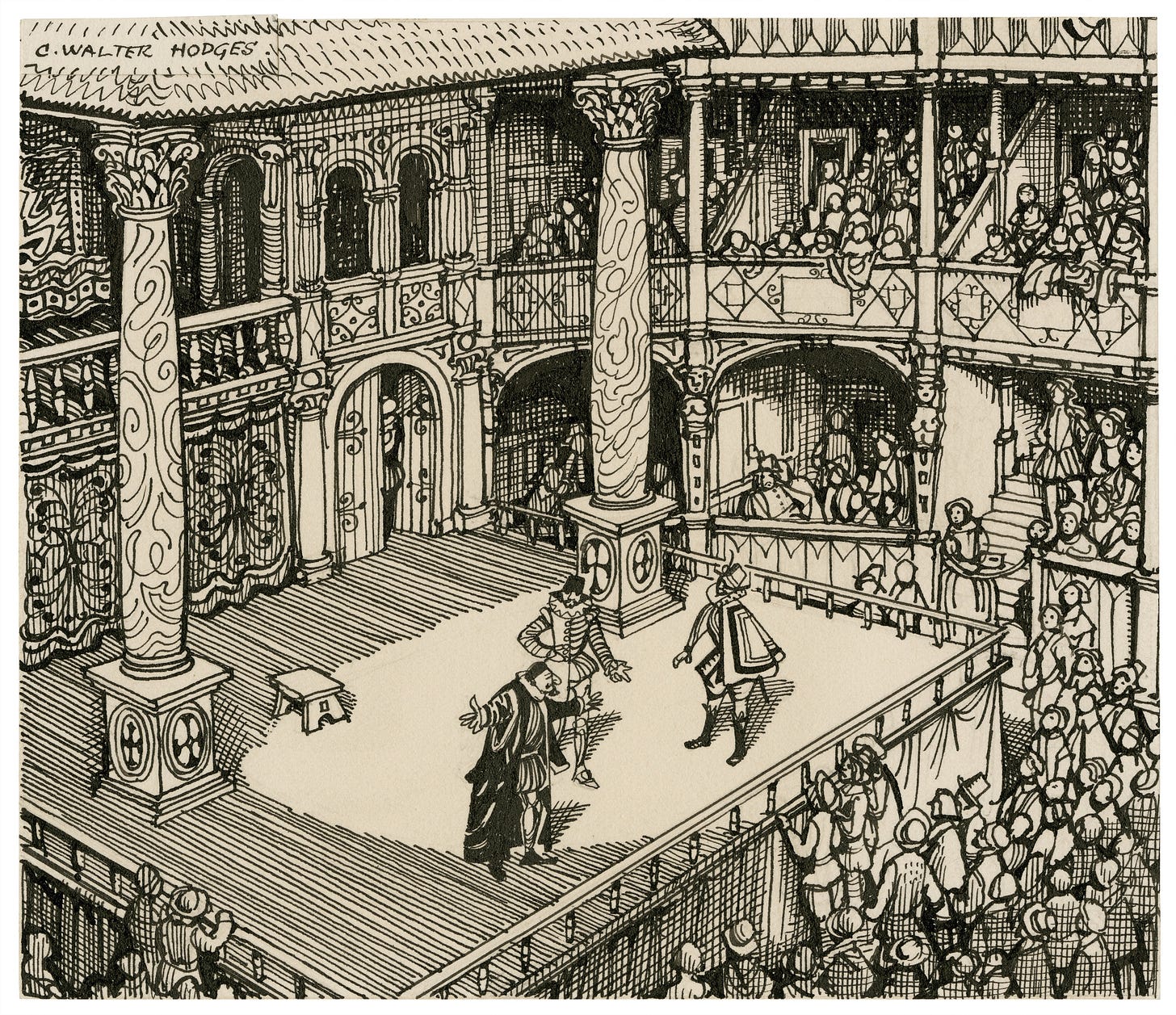

Other forms of leisure and entertainment included tavern games, bowls, and public spectacles, such as bear-baiting, hangings, beheadings, and public autopsies. While theatrical productions had long been offered by companies of itinerant actors, plays produced in specially-built playhouses were a new and popular phenomenon. For a penny, you might see King Lear or Doctor Faustus, if you were willing to be a “groundling.” But if you wanted to have a seat, it would cost a penny more. The best seats in the house could drive the cost up to a shilling (12 pence).4

An Elizabethan theater was sparse with scenery and other props. Costumes were often second-hand purchases from noblemen and women. (It was illegal to wear clothing above your station—except by actors.) The price of a play ticket was cheap, especially for “groundlings,” who paid a penny for standing room. Among them, pickpockets and prostitutes plied their own trades. Bathroom facilities were not included in the price of a ticket, even for those who paid a shilling.

No matter where you were in London, hygiene would be far from hygienic, partly out of ignorance and partly because of limited plumbing and inadequate sewage disposal. As a resident, you would have learned to ignore the stench of cesspits, rendering houses, soapmakers, gluemakers, and tanners, along with street droppings from dogs and horses; public urination was common, adding to the aromatic ambiance. Moreover, bathing was infrequent and inconvenient, particularly because most homes and lodgings had no running water. People relied on frequent changes of underwear to minimize their personal odors, and those who could afford to do so also used perfumes. (Elizabeth was said to bathe once a month, which was considered remarkably often and possibly unhealthy.)5

Yet England was modernizing: it was just that hygiene, plumbing, and many other advances in health and sanitation were not among the earliest things to change as the country left the Middle Ages and entered the Early Modern period.

Feudalism, with its warring dukes, castles, and agrarian economy, had been largely displaced by a more powerful central government and the growth of cities, which were becoming important hubs of international commerce that were making merchants, traders, and bankers wealthy and more influential. Thus, the country was becoming a major power, but one that made it a ripe target for conquest. So, the Elizabethans were rightly worrying about war, especially with Spain and its powerful Armada.

But it was the English Renaissance! The arts and literature were flourishing, as the “rebirth” that began in Italy some two centuries earlier with the Medici, Michelangelo, and Machiavelli made its way to Britannia. A century before, Gutenberg had invented the printing press, so by Elizabeth’s reign, one would see printed materials everywhere in London, often in the form of pamphlets and posters, but also books and copies of poems and plays—yes, by Mr. Shakespeare among many others. Our playwright was just one of a long lineage of luminaries stretching back in time and space from London to Florence. Most English men and women, of course, had no idea that they were participants in such momentous and pivotal times.

If you were living in that London of four hundred years ago, you would likely have been part of a great migration fleeing the life of a country peasant or simply chasing the opportunities you had heard were waiting for you in the cities. There, you were part of a world that was opening up to finance, trade, and new ideas from afar—especially to ideas from the ancient Greeks, Plato and Aristotle among them, that had been lost in Europe but preserved in the East and returned during the Crusades.

Likewise, minds were opening up with the rise of science and the flickers of the Enlightenment that would burgeon shortly after Shakespeare’s death. Education was also becoming more common, especially among the more privileged classes. Males from noble families often had private tutors who taught them reading, writing, and languages, plus some math, astronomy, and art. Gentlemen from the rising professional middle class of traders, physicians, lawyers, merchants, and priests would have attended the universities, although women were not considered suited for higher education. Regardless of class, a woman’s role was to run the household and be a good breeder, perpetuating the family line. Ironically, during most of Shakespeare’s lifetime, the English monarch was Elizabeth, “the Virgin Queen.”6

Still, chances were, had you been a resident of Elizabethan London, you would have been illiterate, whether you were male or female. Estimates put the literacy rate at about thirty percent for men and about ten percent for women.7 While those numbers may seem low, literacy was increasing rapidly, partly because of the “grammar schools” and “petty schools” that Elizabeth had established all over the country. In such schools, students from common families could learn to read (both English and Latin) and do simple math. Ironically, again, Elizabeth’s grammar schools were open only to boys.8

The English Renaissance did not happen abruptly or even in Shakespeare’s lifetime. It was a confluence of events coming from many directions and at different times over several generations. For example, Columbus had “discovered” the Americas nearly a century earlier,9 yet people were still curious about the strange lands and “savages” across the Atlantic. This New World was the context in which he set The Tempest, with its “savages” exemplified by the sprite, Ariel, and the churlish monster, Caliban, whom the wizard Prospero described as:

A devil, a born devil, on whose nature

Nurture can never stick; on whom my pains,

Humanely taken, all, all lost, quite lost.10

- The Tempest (4.1.211)

Almost certainly, you, as an English woman or man, would have been a Christian, although you might have been conflicted about which variant to join. The Reformation had started with Martin Luther in 1517. And it was Elizabeth’s father, the much-married Henry VIII who had brought his own version of the Protestant Reformation to previously-Catholic England. The cause was a dispute with Pope Clement VII over Henry’s petition for a divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, because she failed to produce a male heir. Henry ultimately broke with Rome and established the protestant Church of England.

Henry’s reign was followed by that of his daughter (Bloody) Mary Tudor, who attempted to reestablish Catholicism by butchering and burning Protestant heretics. Elizabeth, Henry’s other daughter, reversed the religious course again, requiring everyone in England to attend the Church of England and persecuted “recusant” Catholics who did not. These reversals of spiritual allegiance might have been problematic for the Shakespeare family, says scholar Stephen Greenblatt, who has argued that the Bard came from a family of closeted Catholics who had managed to survive the religious reversals of the Tudor period11.

What, in those times, would have been your beliefs about the natural world? By the Elizabethan era, educated people had long accepted the notion that the Earth was spherical, not flat. But the Earth’s place in the heavens was not settled. The Roman Church considered Copernicus a heretic for his proposal that the Sun, not the Earth, was the center of the cosmos.12 And when Galileo presented telescopic evidence that some heavenly bodies circle other planets, he was tried by the Inquisition and put under house arrest by Church authorities who demanded the final word on scientific facts.13

Galileo demonstrates his telescope in the Piazza San Marco, Venice. Wood engraving, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. This and all images in this post are in the public domain.

Diseases were also in dispute—variously attributed to foul air, punishments inflicted by God or the Devil, and the ancient theory of the humors. The latter idea, originating in antiquity, proposed that a healthy body required a delicate balance of four body fluids: blood, yellow bile (choler), black bile (melancholer), and phlegm. This theory led to the treatment of disease by bleeding, which physicians of the day believed could flush excessive humors from the body.

Among the most feared in Shakespeare’s England were syphilis (“the pox”), typhoid, cholera, and malaria. Worst of all, the plague, which struck widely and indiscriminately every few years, took about one-fifth of London’s populace. In the Bard’s theatrical heyday, his livelihood suffered from year-long theater closures triggered by plague outbreaks. The plague also called into question the explanations for its cause. Medicine, which had not yet discovered the “germ theory,” was powerless against the plague, nor had physicians discovered the plague’s vectors (rats and fleas). Similarly, as wave after wave of the disease washed over England, people lost hope in a feckless Church’s attempts to deal with it in religious terms—as a punishment by an angry God for a populace turning away from God.

Even without the plague, life could be short: some 30-odd years on average. This statistic was qualified by a high infant mortality rate of about fifty percent by the age of ten. Certainly, some individuals lived into their sixties, seventies, and even eighties, but they were few. So Shakespeare, who died at age 52, was considered to have had a long life.

And how would you and others in this England have understood human nature? Much of what we know about the psychology of Elizabethan England comes from playwrights and poets like Wm. Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and Ben Jonson and the characters they created. Arguably, the Bard’s greatest personality was the boastful, lazy, jovial, corpulent knight, Jack Falstaff—Prince Hal’s best pal in the pubs and stews of London. The following exchange between the two captures the essence of Falstaff’s personality:14

PRINCE HAL: That villainous abominable misleader of youth, Falstaff, that old white-bearded Satan.

FALSTAFF: My lord, the man I know.

PRINCE HAL: I know thou dost.

FALSTAFF: But to say I know more harm in him than in myself were to say more than I know. That he is old, the more the pity; his white hairs do witness it. But that he is, saving your reverence, a whoremaster, that I utterly deny. If sack15 and sugar be a fault, God help the wicked. If to be old and merry be a sin, then many an old host that I know is damned. If to be fat be to be hated, then Pharaoh’s lean kine16 are to be loved. No, my good lord, banish Peto, banish Bardolph, banish Poins, but for sweet Jack Falstaff, kind Jack Falstaff, true Jack Falstaff, valiant Jack Falstaff, and therefore more valiant being, as he is old Jack Falstaff, banish not him thy Harry’s company, banish not him thy Harry’s company. Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world.

– Henry IV, Part 1, 2.4.479

So, how did Shakespeare’s audiences conceive of Falstaff? It was in terms of the humors: the four bodily fluids that they believed were not only responsible for physical health and disease but for temperament and mental disorder. Each humor, in excess or dearth, produced a different mood, temperament, or illness:

Black bile, also known as melancholer, was believed to cause melancholia or what we now call sadness and depression.

Yellow bile, or simply choler, caused one to be short-tempered or aggressive.

Phlegm, or mucus, made a person sluggish and lazy or slow-witted.

Blood was not only a humor but a carrier of the other humors around the body; in abundance, it produced a sanguine personality, full of energy and playfulness.

The humors were a playwright’s delight because everyone in the audience knew about the humors, and they conveyed a character type in a single word, as when Timon (of Athens) says:

Away, thou issue of a mangy dog!

Choler does kill me that thou art alive;

I swound17 to see thee.

In another example, Beatrice alludes to “cold blood” as she responds to Benedick’s protestations that he would never fall in love:

Beatrice: I thank God and my cold blood, I am of your humour for that: I had rather hear my dog bark at a crow than a man swear he loves me.

– Much Ado About Nothing, 1.1.126

Other references merely hinted at the humors. So, audiences would have inferred that Hamlet, the “melancholy Dane,” would be seen as suffering as much from black bile as from suspicions about his father’s murderer. Poets, too, were thought to have personalities dominated by melancholer. Prince Hal, in the days of his youthful indiscretions, would have been viewed as sanguine; so would Falstaff, but his slothfulness also indicated an overabundance of phlegm. And Hal’s nemesis, Henry Percy (nickname: Hotspur), had a character symptomatic of yellow bile or choler.

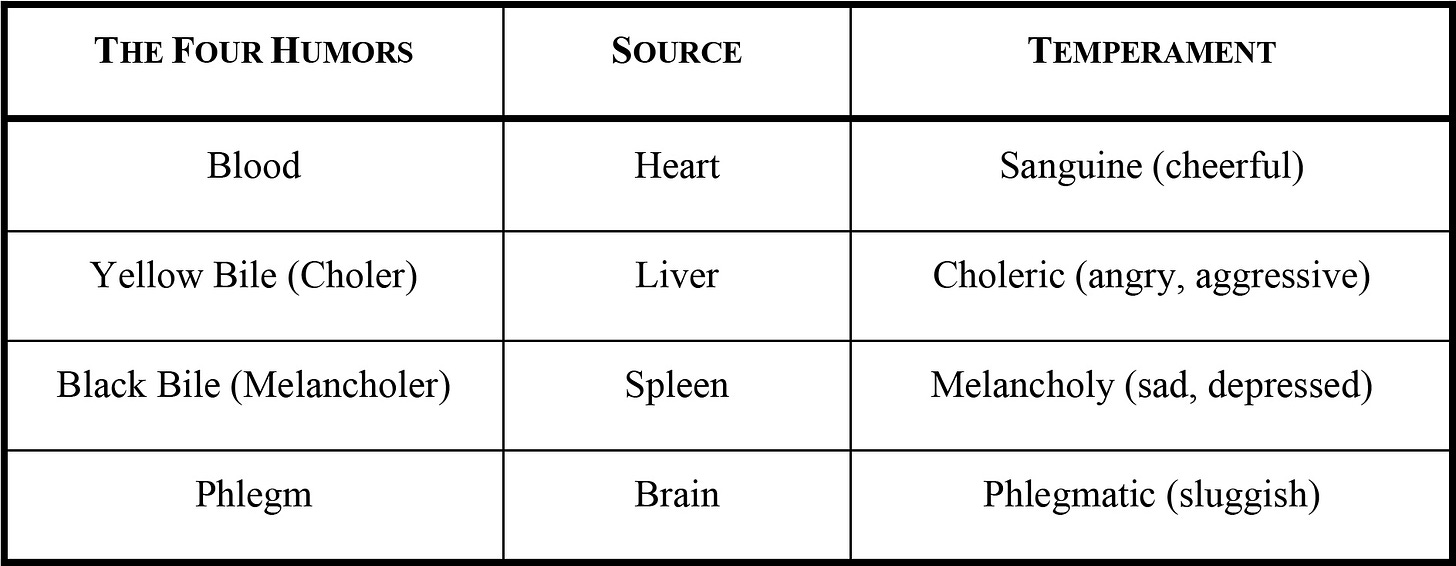

The source of each of the humors is shown in this table from our book, Psychology According to Shakespeare:

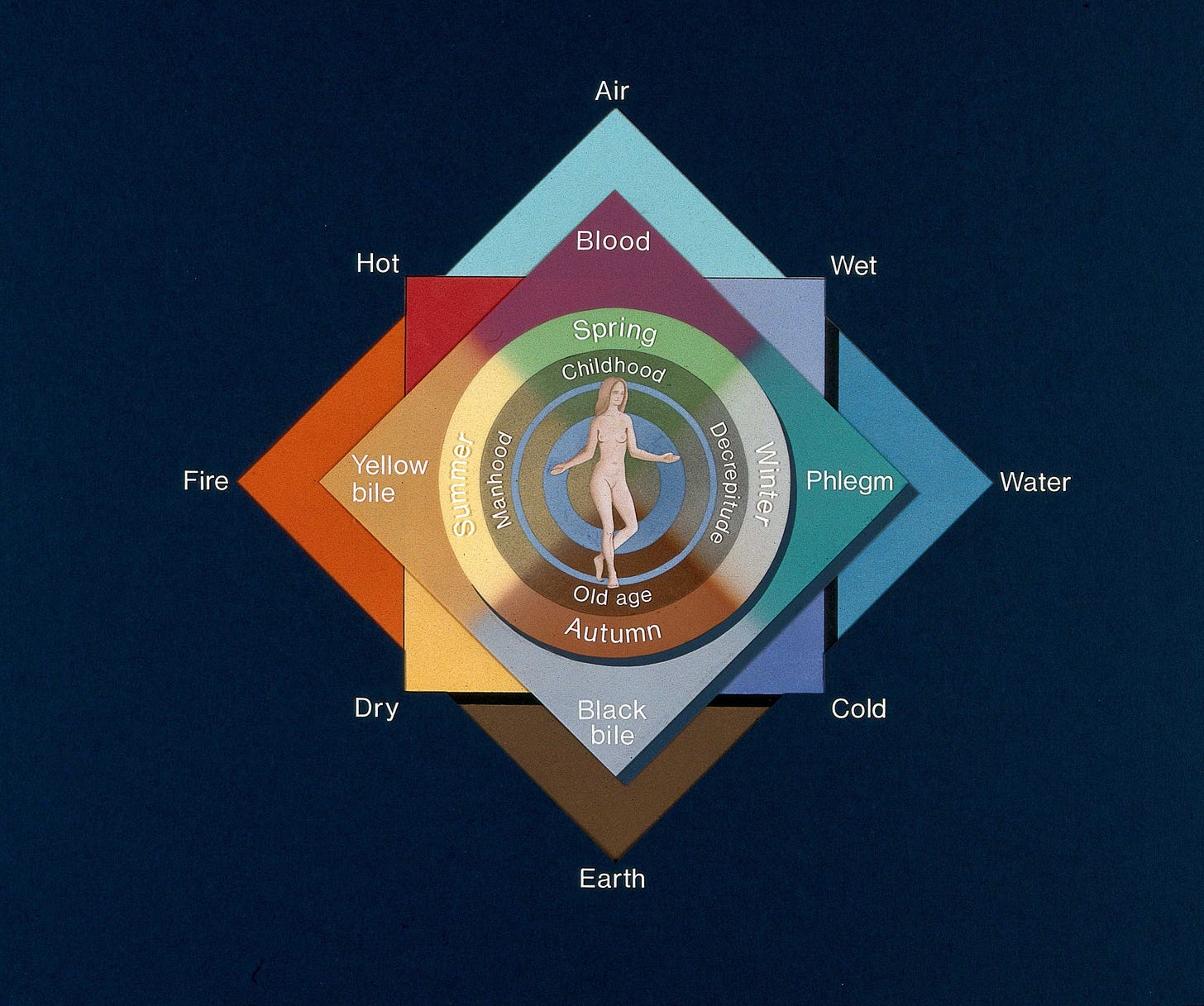

As you can see in the figure below, the humors were part of a much broader view of the Elizabethan universe involving the seasons, stages of life, climate, and the elements.

The relationships between the four humors and qualities of the natural world. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Astrology, too, had a role in the Elizabethan understanding of temperament and personality that depended on which planet was ascendant when you were born. Astrologers were not always in agreement, but Shakespeare’s audiences would have understood the basic connections. Blood and the sanguine personality were associated with Jupiter; choler (yellow bile) suggested warlike Mars; melancholer meant the influence of Saturn; and phlegm was produced under the auspices of Venus and the Moon.

Shakespeare, however, seems to have been skeptical about the influence of the heavens on personality, as we can infer when Cassius says, “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, / But in ourselves,” (1.2.142) or in this lament from King Lear (1.2.125) where we hear Edmund, the bastard son of Gloucester, say:

This is the excellent foppery of the world, that when we are sick in fortune (often the surfeits of our own behavior) we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and stars, as if we were villains on necessity; fools by heavenly compulsion; knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical predominance; drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforced obedience of planetary influence; and all that we are evil in, by a divine thrusting on. An admirable evasion of whoremaster man, to lay his goatish disposition on the charge of a star! My father compounded with my mother under the Dragon’s tail, and my nativity was under Ursa Major, so that it follows I am rough and lecherous. Fut, I should have been that I am, had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on my bastardizing . . . .

In our time, astronomy has long since banished astrology, at least among educated folk, but the idea that the heavens influence personality and temperament had a long run. The humor theory, too, was taken seriously from the time of the ancient Greeks until its removal from medicine as late as the 19th century. Nonetheless, we can still hear echoes of the humors in our language today in our use of the term melancholy or when we hear someone described as phlegmatic, sanguine, or bilious.18 The old humor theory still makes some practical sense, too. It divides personality and temperament into common and familiar categories of people that we observe every day: depressive, aggressive, sluggish, and convivial.

The humors also served as a stepping-stone to important discoveries by modern neuroscience. There are fluid chemicals in our bodies that have huge effects on our moods and personalities because they make communication possible between nerve cells: we call them “neurotransmitters.” And we now know that there are not merely four but dozens of such chemicals, some of which you may have heard—such as dopamine, which gives us feelings of pleasure, and adrenaline, which readies the body for action and produces feelings of excitement and fear.

But that’s not all! Still other chemicals, circulating in the blood, facilitate communication between the brain and other organs, regulating heart rate, blood pressure, blood chemistry, breathing, and delivering sensations of pain. We call these modern humors “hormones.”

What’s the point of all this? Wm. Shakespeare’s time is called the Early Modern Period. England, having recently emerged from the Middle Ages, was no longer a country dominated by agrarian fiefdoms. A time traveler from today would have managed to adjust to life in the London of 1600 much more easily than in the Middle Ages, which were marked by a more rigid class hierarchy, stricter religious standards, and an English language that would have seemed almost unintelligible to us. Psychologically speaking, an Elizabethan’s understanding of human nature and nurture was not terribly different from ours. In brief, Shakespeare’s world was the beginning of our own world in which the Bard’s work holds up a mirror to us.

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider getting a copy of Psychology According to Shakespeare, by Philip Zimbardo and me, published in 2024 by Prometheus Books and available at bookstores everywhere.

Here is a peek at the table of contents, showing the featured plays that illustrate each psychological topic:

Psychology According to Shakespeare

Prologue – Why Shakespeare and Psychology?

Introduction – Shakespeare’s Psychology and the Roots of Genius

Part I: Nature vs. Nurture

Chapter 1 – Nature-Nurture, Neuroscience, and the Brain of the Bard: The Tempest

Chapter 2 – The Ages and Stages of Man (and Woman): As You Like It

Part II: The Person vs. the Situation

Chapter 3 – Henrys, Humors, and the Psychology of Personality: Richard II – Henry V

Chapter 4 – Social Influence from Stratford to Stanford: Measure for Measure

Chapter 5 – Heroes Ancient and Modern, Major and Minor: Othello

Part III: Into the Mind

Chapter 6 – Sleep and Dreams: A Window into the Unconscious: A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Chapter 7 – Mental Illness and Other Ill Humors: Richard III

Part IV: Reason vs. Emotion

Chapter 8 – Emotion, Motivation, and Elizabethan Love: Love’s Labour’s Lost

Chapter 9 – Reason, Intuition, and the Dithering Prince of Denmark: Hamlet

Epilogue – Psychology, Shakespeare, and Beyond

I’m using the term loosely to include the Jacobean era, the reign of King James I, who was also James VI of Scotland. Elizabeth and James were cousins; their common ancestor was Henry Tudor (a.k.a. Henry VII), the fellow who established the Tudor dynasty by defeating Richard III at Bosworth in 1485. James I, however, was the beginning of the Stuart dynasty, which lasted until 1714, enduring much civil strife. To be more precise, the Elizabethan era extended from Elizabeth’s ascent to the throne in 1558 to her death in 1603, when James became king of England. Shakespeare’s lifetime (1564 to 1616) spanned the last years of Elizabeth’s reign and the early portion of King James I’s reign.

Yes, women did go to pubs in Elizabethan times, either alone or with family and friends. Nevertheless, pubs were often male-dominated hangouts.

Jonson, Ben. Discoveries Upon Men and Matter. Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5134/5134-h/5134-h.htm

“Audiences.” Shakespeare’s Globe, 2025: https://www.shakespearesglobe.com/discover/shakespeares-world/audiences/

Munholland, Joanna. “Personal hygiene, Tudor style.” Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, 22 Jan 2016: https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/blogs/personal-hygiene-tudor-style/

How did Elizabeth I’s reign affect the roles of women? See: “Young, female and powerful: Was Elizabeth I a feminist?” Royal Museums Greenwich, 2017: https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/young-female-powerful-was-elizabeth-i-feminist

Whitmore, Michael. “Books and Reading in Shakespeare's England.” Shakespeare Unlimited: Episode 137 (An interview with Stuart Kells). Folger Shakespeare Library, February 4, 2020. https://www.folger.edu/podcasts/shakespeare-unlimited/books-reading/

Cartwright, Michael. “Education in the Elizabethan Era.” World History Encyclopedia. August 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1583/education-in-the-elizabethan-era/

True, if only you ignore my Viking ancestors who were the second people to discover North America, as early as 1021, nearly five hundred years before Chris Columbus. The people we call Native Americans did so some 29,000 years earlier than the Norse. Kuitens, Margot, et al. “Evidence for European presence in the Americas in 1021” Nature, 2021, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03972-8

This quote is arguably the first pairing of the terms “nature-nurture,” a foundational concept in psychology some four hundred years later.

Greenblatt, Stephen. “Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare.” W. W. Norton, 2005.

Copernicus remained a Catholic throughout his life, even though his heliocentric theory was considered heretical. Interestingly, it was some Swiss Protestants who raised the first objection to his theory. See: Weibel, Thomas. “Copernicus the Heretic.” Swiss National Museum, July 19, 2022, https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/en/2022/07/copernicus-the-heretic/

Galileo and Shakespeare were both born in 1564.

This exchange is part of a longer conversation between Prince Hal and Falstaff, who are rehearsing for a difficult conversation that Hal anticipates with his father, Henry IV. Hal thinks that his father will demand that the prince cease carousing with Falstaff, and so they are role-playing that encounter, with Hal playing the part of the king and Falstaff playing the part of Prince Hal.

Sack, Falstaff’s favorite fluid, is a sherry or fortified sweet white wine, to which brandy or other spirits have been added. Often, sack was imported from Spain.

Kine is an archaic term for cattle. Here, Falstaff makes a biblical reference to Pharaoh’s dream in which seven lean kine emerged from the river and ate seven fat kine. Joseph interpreted the dream as foretelling seven years of good harvests followed by seven years of famine.

swoon

We now know that there is only one kind of bile, and it has no effect on personality (but it does help us digest fats and eliminate excess cholesterol).